Article continues below

The German city of Mainz lies on the banks of the River Rhine. It is most notable for its wine, its cathedral and for being the home of Johannes Gutenberg, who introduced the printing press to Europe. Although these things may seem unconnected at first, here they overlap, merging and influencing one another.

The three elements converge on market days, when local producers and winemakers sell their goods in the main square surrounding the sprawling St Martin's Cathedral. Diagonally opposite is the Gutenberg Museum , named after the city’s most famous inhabitant, who was born in Mainz around 1399 and died here 550 years ago in 1468.

The printing press marks the turning point from medieval times to modernity in the Western world

It was Gutenberg who invented Europe’s first movable metal type printing press, which started the printing revolution and marks the turning point from medieval times to modernity in the Western world. Although the Chinese were using woodblock printing many centuries earlier, with a complete printed book, made in 868, found in a cave in north-west China, movable type printing never became very popular in the East due to the importance of calligraphy, the complexity of hand-written Chinese and the large number of characters. Gutenberg’s press, however, was well suited to the European writing system, and its development was heavily influenced by the area from which it came.

The German city of Mainz is most notable for being the home of Johannes Gutenberg, the inventor of the movable metal type printing press (Credit: Madhvi Ramani)

You may also be interested in: • Where wireless communication was born • The shipyard that changed humanity • The island that forever changed science

In the Middle Ages, Mainz was one of the most important cathedral cities in the Holy Roman Empire, in which the Church and the archbishop of Mainz were the centre of influence and political power. Gutenberg, as an educated and entrepreneurial patrician, would have recognised the Church’s need to update the method of replicating manuscripts, which were hand-copied by monks. This was an incredibly slow and laborious process; one that could not keep up with the growing demand for books at the time. In his book, Revolutions in Communication: Media History from Gutenberg to the Digital Age , Dr Bill Kovarik, professor of communication at Radford University in the US state of Virginia, describes this capacity in terms of ‘monk power’, where ‘one monk’ equals a day’s work – about one page – for a manuscript copier. Gutenberg’s press amplified the power of a monk by 200 times.

At the Gutenberg Museum, I watched a demonstration of a page being printed on a replica of the press. First, a metal alloy was heated and poured into a matrix (a mould used to cast a letter). Once the alloy cooled, the small metal letters were arranged into words and sentences in a form and inked. Finally, paper was placed on top of the form and a heavy plate was pressed upon it, similar to how a wine press works. This is no coincidence: Gutenberg’s printing press is thought to be a modification of the wine press. Since the Romans introduced winemaking to the region, the area around Mainz has been one of Germany’s main wine-producing areas, with famous grape varieties such as riesling, dornfelder and silvaner.

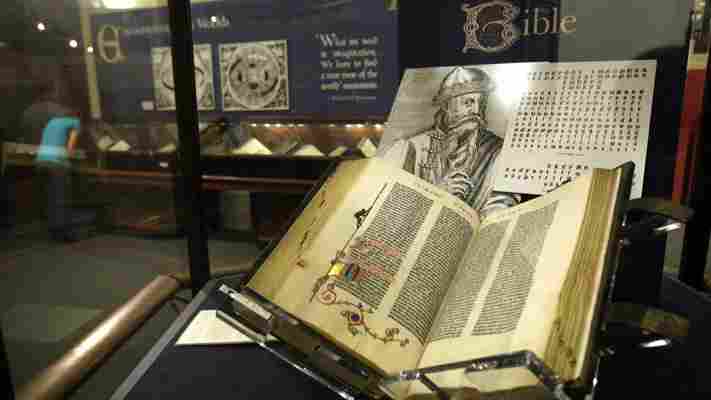

The page that is always printed at the Gutenberg Museum replicates the original style and font (Gothic Textura) of the 42-line Gutenberg Bible, the first major book ever to be printed using movable type in the Western world. It is the first page of St John’s Gospel, in the Bible, which begins: “In the beginning was the word…”

Gutenberg’s printing press made it easier for the Church to replicate religious manuscripts (Credit: Madhvi Ramani)

Writing is often considered the first communication revolution, while Gutenberg’s printing press brought with it the revolution of mass communication. After about 15 years of development – and huge capital investment – Gutenberg printed his first Bible in 1455.

“Gutenberg's Bible is an extraordinary work of craftsmanship,” said Dr Kovarik, who suggests we can read a strong religious motivation into the perfection of his work. “This wasn’t unusual at the time – for example, a stonemason would try to achieve a perfect sculpture in a remote corner of one of the great cathedrals, not really for the people who would be worshipping there, but rather as an expression of personal faith.”

Gutenberg’s printing press brought with it the revolution of mass communication

Of his original print run of about 150 to 180 Bibles, only 48 remain in the world today. The Gutenberg Museum has two on display. Both are slightly different, because after printing, the pages would be taken to a rubricator (specialised scriber) who would paint in certain letters according to the tastes of their customers. Gutenberg’s Bibles turned out to be bestsellers.

At first, the Church welcomed the new availability of printed bibles and other religious texts. Printing enabled the Church to spread the Christian message and raise cash in the form of ‘indulgences’ – printed documents that forgave people’s sins. However, the disruptive power of the printed word soon became apparent. With the rapid spread of printing technology – by the 1470s, every European city had printing companies, and by the 1500s, an estimated four million books had been printed and sold — came the spread of new and often contradictory ideas, such as Martin Luther’s 95 Theses , in which he criticised the Church’s sale of indulgences. Luther is said to have nailed his text to a Wittenberg church door on 31 October 1517. Within a few years 300,000 copies of it had been printed and circulated, leading to the Reformation and a permanent split in the Church.

Of the 150 to 180 Bibles Gutenberg originally printed, only 48 remain in the world today (Credit: Ann Johansson/Getty Images)

But despite the far-reaching consequences of Gutenburg’s press, much about the man remains a mystery, buried deep beneath layers of Mainz history. A plaque marks the place where he was born on corner of Christofsstraße, but the original house is long gone. Today, a modern building stands there, occupied by a pharmacy.

Another plaque outside the nearby St Christoph’s Church marks the place where he was likely baptised. The church was bombed during World War II and remains in ruins as a war memorial, although the original baptismal font from Gutenberg’s time is still intact.

The graveyard where Gutenberg was buried has been paved over, and even though there are statues of him are everywhere in the city, we don’t know what he looked like. He is commonly depicted with a beard, but it is unlikely that he had one. Gutenberg was a patrician and during his time, according to my tour guide Johanna Hein, only pilgrims and Jews wore beards. In fact, the man we all know as Johannes Gutenberg was actually born Johannes Gensfleisch (which translates to ‘goose meat’). If it weren’t for the 14th-Century trend of people renaming themselves after their houses, we would perhaps be referring to his invention as the Gensfleisch Press today.

Despite the far-reaching consequences of his printing press, little is known about Gutenberg today (Credit: Madhvi Ramani)

But although the traces of the man have all but disappeared from the city, his influence can still be seen everywhere: a poster advertising cosmetics; a woman reading a newspaper in a cafe; the menu on a restaurant table. Furthermore, our current communications revolution, made possible by the internet, digital technology and social media, is a progression of what started with Gutenberg.

“Every time the cost of media declines rapidly, you enable more people to speak out, and you have a greater diversity of voices,” said Dr Kovarik, explaining that this impacts the distribution of power in society, and sparks social change.

Although the traces of Gutenberg have all but disappeared from the city, his influence can still be seen everywhere (Credit: Lebrecht Music and Arts Photo Library/Alamy)

Paradoxically, however, our digital revolution can also be seen as a return to the pre-print era, according to a theory called The Gutenberg Parenthesis by Dr Thomas Pettitt, affiliate research professor at the University of Southern Denmark, who argues that there are parallels between the pre-print age and our own internet age.

In the absence of print, news has lost its authenticity, and, as in the Middle Ages, is synonymous with rumour

“Print conferred stability on discourse; works in books were authorities; news in print was true. In the absence of print, news has lost its authenticity, and, as in the Middle Ages, is synonymous with rumour. We are now in a post-news phase, where purveyors of fake news can accuse the legitimate press of purveying fake news and get away with it,” Dr Pettitt said.

Whatever the impact of the 21st-Century digital revolution, just like the printing revolution before it, the effects will reverberate for hundreds of years to come.

Places That Changed the World is a BBC Travel series looking into how a destination has made a significant impact on the entire planet.

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook , or follow us on Twitter and Instagram .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Travel, Capital, Culture, Earth and Future, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Leave a Comment