Article continues below

“We’re a Victorian institution,” black-cab driver Henry announced proudly, tugging on his tartan cap. It was a grey mid-morning in London and I was squeezed in a small green shed behind a narrow, U-shaped table. Surrounding me were a cluster of taxi drivers who slurped on mugs of tea and shovelled in forkfuls of scrambled egg and sausage.

This diminutive shed in Russell Square is where the keepers of London’s secrets gather – the black-cab drivers whose minds are mapped with every inch of the city. It’s one of 13 cabmen’s shelters remaining in the capital, and only licensed drivers who have passed The Knowledge test – memorising every street, landmark and route in London – are allowed inside.

Thirteen historical cabmen’s shelters can be found throughout London (Credit: Chris J Ratcliff/Getty Images)

You may also be interested in: • A strange London life that few know • London’s secret underground mail rail • The bread that changed how the Irish eat breakfast

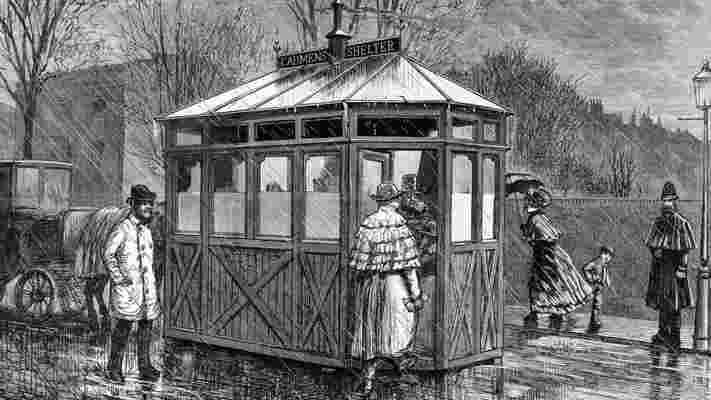

The idea for the shelters came in the late 19th Century when George Armstrong, a year before he became editor of The Globe newspaper, was unable to hail a taxi during a blizzard because the drivers, who then rode horse-drawn hansom cabs, were huddled in a nearby pub. He teamed up with philanthropists, including the Earl of Shaftesbury, to find a way to keep drivers on the straight and narrow – and off the drink.

The Cabmen’s Shelter Fund was born in 1875, building the first hut in St John’s Wood. It still operates today, though many of the further 60 huts built have since been knocked down.

This is where the keepers of London’s secrets gather

Each hut was built no bigger than a horse and cart, in line with Metropolitan Police rules because they stood on public highways. They provided shelter and sustenance for hackney-carriage (black-cab) drivers, with strict rules against swearing, gaming, gambling and drinking alcohol.

Then came World War I. Drivers and their vehicles were drafted, plunging the cab trade – and the shelters – into decline. “We lost people, cars and horses,” said Gary, one of the cabbies I chatted to at Russell Square.

Unused, unloved and unprotected, the oak huts suffered rot and ruin. Some were destroyed by bombs during World War II, while many were later bulldozed in street-widening schemes.

Built in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, the green huts provided shelter for the city’s hackney-carriage drivers (Credit: Edward Gooch/Getty Images)

Now just 13 remain, with 10 in operation. Each is Grade II listed, which means they are considered buildings of special interest and every effort should be made to preserve them. They are owned by the Worshipful Company of Hackney Carriage Drivers (WCHCD), a guild for those who earn their living through the trade. The Cabmen’s Shelter Fund is responsible for upkeep and maintenance, issuing annual licences to those who run them.

“The cab trade is very lonely,” said Colin Evans, a cabbie of 44 years and trustee of the fund. “These are places where you can go and have a tea or coffee with your mates. If drivers don’t support them, they will be lost forever.”

Gary, who often comes here for a tea and a grumble because “everyone’s in the same boat”, added: “I’ve been driving a cab for more than a few years and only recently started using the shelters. I decided, use them or lose them.”

The cabmen’s shelters are no larger than a horse and cart, and only drivers are allowed in (Credit: Chris J Ratcliff/Getty Images)

Most serve breakfast (sausages, eggs, bacon), sandwiches and hot drinks, with the occasional pie or lasagne cooked by the owners at home and reheated in the skinny kitchens. Non-cabbies aren’t allowed to sit inside – unless issued with a rare invitation – but can order through a window hatch.

“We bring in more money that way,” said Jude Holmes, who runs the kitchen at Russell Square. “I can serve hundreds of people while a driver sits with one cup of tea.”

It’s like their second home

As we sat there, a relentless drizzle outside drew more cabbies through the door, each greeting the others like family members.

“My little gang comes in every day,” Holmes said. “I worry a bit if I don’t see them. It’s like their second home. Sometimes they even make their own tea.” She added that newer drivers are often too intimidated to come inside, preferring to order bacon sandwiches at the window.

“It can feel a bit cliquey at times,” Gary admitted.

Card playing and gambling are prohibited inside London's cabmen's shelters (Credit: Ella Buchan)

The kettle bubbled, teaspoons clinked against china, and bacon spluttered and sizzled in a pan as talk turned to the cabbies’ biggest bugbears. Being ‘bilked’, for example, when a fare runs off without paying. Struggling to find a public lavatory when on the job is another common groan (the shelters don’t have loos).

Most drivers have other gigs, as musicians, artists, TV producers, even actors. But, they told me, once a cabbie – always a cabbie. “If you retire, you die,” Gary deadpanned.

The anecdotes poured faster than the tea. There’s the tale of ‘Fat Ray’, so huge he squeezes himself behind the wheel each morning and doesn’t budge until he gets home. “He couldn’t come in ’ere,” said Henry, sweeping his hand around the shelter. “He’d never fit through the door!”

Most cabmen’s shelters serve breakfast, sandwiches and hot drinks (Credit: Chris J Ratcliff/Getty Images)

Evans took me for a spin in his cab, stopping by Temple Place shelter on Victoria Embankment, where a team was fixing damage caused by a lorry.

The shelters’ Grade II status means restoration is intricate and expensive. Refurbishment costs around £30,000, Evans estimated, and replacement materials must match the originals. Even the shade of paint – Dulux Buckingham Paradise 1 Green – is prescribed to mirror the first huts.

They represent a moment in time

Shelters have also been hit by noise restrictions in residential areas, and none currently operate at night – most open around 07:00 and close by 13:00. A hut at Chelsea Embankment has been closed for five years due to parking restrictions, and the fund is considering donating it to the London Transport Museum .

Crucially, said Evans, these tiny huts must not disappear – nor should their history be forgotten. “It’s too easy to get rid of these things. The shelters are unique. They represent a moment in time.”

Jude Holmes also sells snacks to the public through the hatch of the Russell Square shelter (Credit: Ella Buchan)

It’s true there’s plenty of history packed within their walls. Evans told me that the Gloucester Road shelter was nicknamed ‘The Kremlin’ because it was frequented by left-wing drivers. The since-bulldozed Piccadilly hut was the site of Champagne-fuelled parties in the 1920s and dubbed the ‘Junior Turf Club’ – after an exclusive gentlemen’s club nearby – by (non cab-driver) aristocratic revellers who smuggled in booze.

And according to local legend, a man claiming to be Jack the Ripper once visited Westbourne Grove shelter.

Physical signs of their history remain. Tenders attached to the bottom of the huts were where drivers tethered their horses before going inside. The animals drank from marble troughs, now gone. Each shelter still has a rooftop vent with ornate carvings – reminders of the wood-burning stoves once used for heating and cooking.

In the Warwick Avenue shelter, shelves are lined with cabbies’ mugs bearing the names of their football teams (Credit: Ella Buchan)

We continued onto Warwick Avenue shelter, frequented by musicians and actors who live nearby. British mod-rocker Paul Weller, former lead singer of The Jam and The Style Council, often comes to the hatch for a sausage-and-egg sandwich, licensee Tracy Tucker told me.

Tucker, whose husband is a cabbie, has been a shelter keeper for 14 years, moving to this location from Thurloe Place in 2016. The roof was recently re-shingled at a cost of £13,000, financed by the fund.

Inside, the tiny kitchen has a stovetop sizzling with sausages and bacon, a fridge stocked with sandwich fillings and shelves heaving with cabbies’ mugs bearing the crests of their football teams. When someone’s team is relegated or loses a big match, Tucker ties a black ribbon to their mug’s handle in commiseration.

Tracy Tucker, who runs the Warwick Avenue shelter, sees her regulars as family (Credit: Ella Buchan)

To her regulars, Tucker is family.

“They see me as a big sister,” she said. “If I’m sick, I have to text about 20 people to say the shelter is closed. Some of them won’t know what to do with themselves.”

If we lose this, we lose part of London history

She has her own rules: no staring at mobile phones and no moaning about Uber. “We all know it’s quiet. The trade is dying, and I have thought about what I would do if I had to get another job. I don’t think I could work anywhere else.”

“The little lives that go on in these shelters,” chuckled Evans as we pulled away. “It’s not just the buildings. It’s the characters, too. If we lose this, we lose part of the cab trade’s history and a part of London history. That would be a real shame.”

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook , or follow us on Twitter and Instagram .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Travel, Capital, Culture, Earth and Future, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Leave a Comment